|

The workshop is an expanded, transparent process which attempts a critical assessment in detail. I hope this will be a collaborative, constructive mechanism with contributions from anyone who feels up to it. The writer too can come back to correct any misreadings or even ask for the entire critique to be removed. A simple “That’s all bollocks Ken” should do the trick. I don’t, of course, claim to be the final arbiter of taste. I’m just another reader with prejudices and blind spots. I do, however, believe strongly in re-writes – lots of them – and the importance of even tiny adjustments to improve tone and flow. I guess some of my tweaks will look like nit-picking but the default mode of first drafts (mine included) is pox doctor’s clerk – an over explained, unnecessarily detailed account such as PC Plod might come up with in court. Considerations as to the commercial potential of the offering are entirely irrelevant. What we’re aiming at is the best presentation of the crazy oik’s vision. Or as Delacroix said of his rival Ingres “The perfect expression of an imperfect mind” In the Repair Shop Heat - Brett Wilson Background Texts on Writing

Reality Hunger: A Manifesto –

David Shields Reality Hunger: A Manifesto – David Shields reviewed by Blake Morrison Most readers will know the feeling. You've been through an experience so consuming that you've no room in your head for made-up stories – or the recent choices at your book club have been dire. Either way, novels seem pointless. Why devote precious time to contrived plots and imagined scenarios? Why waste energy on invented characters? Only the real excites you: life writing, memoir, confessional poetry, witness statements from the front line. There's a name for this condition: fiction fatigue. Readers who've experienced it will also know that it usually passes: time heals, the world opens up again and your faith in the novel is restored. David Shields hasn't been cured. He doesn't want to be cured. He thinks of "reality hunger" not as a sickness but as the defining spirit of our age, with its yearning for the music of what happens. His book is a spirited polemic on behalf of non-fiction – a manifesto in 618 soundbites. The book comes laden with praise. Jonathan Lethem, Geoff Dyer, Frederick Barthelme, Rick Moody and Jonathan Raban are among the 20-plus authors whose endorsements dominate the cover and end-pages (though intriguingly JM Coetzee's name, prominent on the proof copy, has disappeared). Some of the acclaim comes from writers whose work Shields cites to support his argument. Still, they're right to call Reality Hunger an important book. The fiction vs non-fiction debate has become intense in recent years, and Shields cranks it up a notch. Every artistic movement is a bid to get closer to reality, he argues, and it's in lyric essays, prose poems and collage novels (as well as performance art, stand-up comedy, documentary film, hip-hop, rap and graffiti) that such impetus is to be found today. Key components include randomness, spontaneity, emotional urgency, literalism, rawness and self-reflexivity. A loosely defined genre, then: in fact, a genre committed to genre-busting. But a genre opposed to current fiction. Early novels such as Robinson Crusoe passed themselves off as true. And at best the novel has always been hybrid, Shields says, with autobiography, history and topography part of the mix – hence his admiration for VS Naipaul and WG Sebald, and their "necessary post-modernist return to the roots of the novel as an essentially creole form". By contrast, the sort of novel that wins the Pulitzer or Booker has "never seemed less central to the culture's sense of itself". Fabrication's a bore. Characterisation a puerile puppet-show. Plot the altar on which interest is sacrificed – only when it's absent are we given room to think. "If I'm reading a book and it seems truly interesting," Shields confesses, "I tend to start reading back to front in order not to be too deeply under the sway of progress." What he wants is distilled wisdom, and he's no longer willing to trudge through 700 pages to find it. He couldn't open Jonathan Franzen's The Corrections if his life depended on it – not because it's a bad book, necessarily, but because "something has happened to my imagination, which can no longer yield to the embrace of novelistic form". Shields maps out the personal journey behind his polemic. As the son of two journalists, he grew up with a respect for reportage, but he also dreamed of a life consecrated to art. His first two novels were linear. Fluency and directness didn't come naturally, though (he'd had a bad childhood stutter), and realist fiction soon proved a dead end. Then one day he had an epiphany in the shower – an idea of juxtaposing fragments and seeing how that looked – and now he can't work any other way. His subsequent books have all been non-fiction, though if altering the facts makes a better story then he alters them. "Don't mess with Mr In-Between," his father used to say, but that's the ground Shields likes to occupy: neither straightahead journalism nor airtight art, but a no man's land of unverifiable authenticity. All the best stories are true, or pretend to be true, and memoir is a seductive form for that reason. But Shields is keen to stress the unreliability of memoir, since "anything processed by memory is fiction". And where a non-fiction narrative follows an obvious pattern (triumph against the odds, etc), it will fail just as fiction fails by being mechanical and manipulative. That's where the advantages of the lyric essay lie: it isn't formulaic; it mirrors the contingency of life. What Shields means by the lyric essay isn't entirely clear. But he talks of rawness rather than polish, and it's safe to say he isn't thinking of Addison or Steele. He quotes Emerson and Montaigne a lot. Proust, though a novelist, is also enrolled, because "nothing ever happens" in his fiction. Crucial to the lyric essay is the lack of any obligation to tell stories. Shields's other great buzzword is collage. He loves cut-ups, mosaics, found objects, chance creations, assemblages, splicings, remixes, mash-ups, homages; the author as "a creative editor, presenting selections by other artists in a new context and adding notes of his own". The novel is dead; long live the anti-novel, built from scraps: "I am quite content to go down to posterity as a scissors-and-paste man," he says. Well, actually, he doesn't say it, James Joyce did. But there are no quotation marks to make that clear, and deliberately so: the book's premise is that "reality can't be copyrighted" and that we all have (or ought to have) ownership of each other's words. True, Shields has been forced to list his citations in small-print footnotes at the back of the book. But he invites readers to remove these with a razor blade, and in the main text we can't tell whether it's him or someone else talking. There are other oddities, such as a chapter in which he reproduces letters he wrote to friends about their books without disclosing what those books are. And there are frustrations, not least with his discussion of reality TV, which fails to explore what, if anything, The Apprentice and American Idol have to do with reality. The real problem, though, is the central thesis. It's smart, stimulating and aphoristic, even when the aphorisms are stolen. But the more you think about it, the dodgier it seems. First there's the relativism about truth and lies. In a chapter entitled "Trials by google" Shields defends (among others) James Frey for making things up in his memoir A Million Little Pieces. Of course Frey made things up, says Shields: who doesn't? Who cares? But there's a difference between false memory, rough recall, wilful deception and exaggeration for dramatic effect. And if Frey is, as Shields says, "a terrible writer", why defend him at all, since he's failed the first test? Carelessness with the truth and aesthetic failure aren't easily disentangled. We believe Primo Levi's account of the Holocaust because of the trouble he takes with small details, whereas the fuzzily predictable memories of Binjamin Wilkomirski's Fragments betray its fraudulence. Second, Shields's excitement with the zeitgeist sometimes leads him down blind alleys. Take Sebald, who has replaced Raymond Carver as the doyen of creative writing programmes, much as Carver once replaced Angela Carter. Shields enlists Sebald in the cause of post-modernism, and it's true that Sebald blurs the margins between fact and fiction. But his voice is that of a German Romantic, half in love with death and decay. His art has nothing to do with blogging, podcasts and YouTube. And, seductive though his example is, a literary culture composed entirely of Sebald imitators, writing lyric essays and prose poems, would be arid. Third, as Zadie Smith has argued, Shields sells fiction short. "Conventional fiction teaches the reader that life is a coherent, fathomable whole," he claims. Does it? Isn't this patronising to novelist and reader alike? Can't wresting order out of chaos be a triumph against the odds? And what exactly is this hated creature, the "conventional" or "standard" novel? The premise is that because life is fragmentary, art must be. But poems that rhyme needn't be a copout. And novels with a clear plot and definite resolution can still be full of ambiguity, darkness and doubt. By the same token, to engage with the dilemmas of an imaginary character means learning to empathise with otherness, and few skills are more important in the world today. Shields has written a provocative and entertaining manifesto. But in his hunger for reality, he forgets that fiction also offers the sustenance of truth. Elmore Leonard's Rules for Writing 1 Never open a book with weather. If it's only to create atmosphere, and not a character's reaction to the weather, you don't want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways than an Eskimo to describe ice and snow in his book Arctic Dreams, you can do all the weather reporting you want. 2 Avoid prologues: they can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in non-fiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want. There is a prologue in John Steinbeck's Sweet Thursday, but it's OK because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: "I like a lot of talk in a book and I don't like to have nobody tell me what the guy that's talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks." 3 Never use a verb other than "said" to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But "said" is far less intrusive than "grumbled", "gasped", "cautioned", "lied". I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with "she asseverated" and had to stop reading and go to the dictionary. 4 Never use an adverb to modify the verb "said" . . . he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances "full of rape and adverbs". 5 Keep your exclamation points under control. You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful. 6 Never use the words "suddenly" or "all hell broke loose". This rule doesn't require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use "suddenly" tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points. 7 Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly. Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won't be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavour of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories Close Range. 8 Avoid detailed descriptions of characters, which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway's "Hills Like White Elephants", what do the "American and the girl with him" look like? "She had taken off her hat and put it on the table." That's the only reference to a physical description in the story. 9 Don't go into great detail describing places and things, unless you're Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language. You don't want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill. 10 Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. My most important rule is one that sums up the 10: if it sounds like writing, I rewrite it. Creative Writing – Can it be taught or is it a scam? Selections from the Paris Review Interviews

1. William Styron - PR Interviews Vol 4 INTERVIEWER What value does the creative-writing course have for young writers? STYRON It gives them a start, I suppose. But it can be an awful waste of time. Look at those people who go back year after year to summer writers' conferences. You get so you can pick them out a mile away. A writing course can only give you a start, and help a little. It can't teach writing. The professor should weed out the good from the bad, cull them like a farmer, and not encourage the ones who haven't got something. At one school I know in New York, which has a lot of writing courses, there are a couple of teachers who moon in the most disgusting way over the poorest, most talentless writers, giving false hope where there shouldn't be any hope at all. Regularly they put out dreary little anthologies, the quality of which would chill your blood. It's a ruinous business, a waste of paper and time, and such teachers should be abolished. INTERVIEWER The average teacher can't teach anything about technique or style? STYRON Well, he can teach you something in matters of technique. You know—don't tell a story from two points of view and that sort of thing. But I don't think even the most conscientious and astute teachers can teach anything about style. Style comes only after long, hard practice and writing. INTERVIEWER Do you enjoy writing? STYRON I certainly don't. I get a fine, warm feeling when I'm doing well, but that pleasure is pretty much negated by the pain of getting started each day. Let's face it, writing is hell. 2. E.B White - PR Interviews Vol 4 INTERVIEWER Is style something that can be taught? WHITE I don't think it can be taught. Style results more from what a person is than from what he knows. But there are a few hints that can be thrown out to advantage. INTERVIEWER What would these few hints be? WHITE They would be the twenty-one hints I threw out in Chapter V of The Elements of Style. There was nothing new or original about them, but there they are, for all to read. 3. P.G. Wodehouse - PR Interviews Vol 4 INTERVIEWER If you were asked to give advice to somebody who wanted to write humorous fiction, what would you tell him? WODEHOUSE I'd give him practical advice, and that is always get to the dialogue as soon as possible. I always feel the thing to go for is speed. Nothing puts the reader off more than a great slab of prose at the start. I think the success of every novel—if it's a novel of action—depends on the high spots. The thing to do is to say to yourself, Which are my big scenes? and then get every drop of juice out of them. The principle I always go on in writing a novel is to think of the characters in terms of actors in a play. I say to myself, if a big name were playing this part, and if he found that after a strong first act he had practically nothing to do in the second act, he would walk out. Now, then, can I twist the story so as to give him plenty to do all the way through? I believe the only way a writer can keep himself up to the mark is by examining each story quite coldly before he starts writing it and asking himself if it is all right as a story. I mean, once you go saying to yourself, This is a pretty weak plot as it stands, but I'm such a hell of a writer that my magic touch will make it okay—you're sunk. If they aren't in interesting situations, characters can't be major characters, not even if you have the rest of the troop talk their heads off about them. 4. Marilynne Robinson - PR Interviews Vol 4 INTERVIEWER What is the most important thing you try to teach your students? ROBINSON I try to make writers actually see what they have written, where the strength is. Usually in fiction there's something that leaps out—an image or a moment that is strong enough to center the story. If they can see it, they can exploit it, enhance it, and build a fiction that is subtle and new. I don't try to teach technique, because frankly most technical problems go away when a writer realizes where the life of a story lies. I don't see any reason in fine-tuning something that's essentially not going anywhere anyway. What they have to do first is interact in a serious way with what they're putting on a page. When people are fully engaged with what they're writing, a striking change occurs, a discipline of language and imagination. 5. John Gardner - PR Interviews Vol 2 INTERVIEWER What about the teaching of creative writing? GARDNER When you teach creative writing, you discover a great deal. For instance, if a student's story is really wonderful but thin, you have to analyze to figure out why it's thin, how you could beef it up. Every discovery of that kind is important. When you're reading only classical and medieval literature, all the bad stuff has been filtered out. There are no bad works in either Greek or Anglo-Saxon. Even the ones that are minor are the very best of the minor, because everything else has been lost or burned or thrown away. When you read this kind of literature, you never really learn how a piece can go wrong, but when you teach creative writing, you see a thousand ways that a piece can go wrong. So it's helpful to me. The other thing that's helpful when you're teaching creative writing is that there are an awful lot of people who at the age of seventeen or eighteen can write as well as you do. That's a frightening discovery. So you ask yourself, What am I doing? Here I've decided that what I'm going to be in life is to be this literary artist, at best; I'm going to stand with Tolstoy, Melville, and all the boys. And there's this kid, nineteen, who's writingjust as well. The characters are vividly perceived, the rhythm in the story is wonderful. What have I got that he hasn't got? You begin to think harder and harder about what makes great fiction. That can lead you to straining and overblowing your own fiction, which I've done sometimes, but it's useful to think about. INTERVIEWER What are some specific things you can teach in creative writing? GARDNER When you teach creative writing, you teach people, among other things, how to plot. You explain the principles, how it is that fiction thinks. And to give the kids a sense of how a plot works, you just spin out plot after plot after plot. In an hour session, you may spin out forty possible plots, one adhering to the real laws of energeia, each one a balance of the particular and general—and not one of them a story that you'd really want to write. Then one time, you hit one that catches you for some reason—you hit on the story that expresses your unrest. When I was teaching creative writing at Chico State, for instance, one of many plots I spun out was The Resurrection. INTERVIEWER How does this work? GARDNER One plot will just sort of rise above all the others for reasons that you don't fully understand. All of them are interesting, all of them have interesting characters, all of them talk about things that you could talk about, but one of them catches you like a nightmare. Then you have no choice but to write it—you can't forget it. It's a weird thing. If it's the kind of plot you really don't want to do because it involves your mother too closely, or whatever, you can try to do something else. But the typewriter keeps hissing at you and shooting sparks, and the paper keeps wrinkling and the lamp goes off and nothing else works, so finally you do the one that God said you've got to do. And once you do it, you're grounded. It's an amazing thing. For instance, before I wrote the story about the kid who runs over his younger brother ("Redemption"), always, regularly, every day I used to have four or five flashes of that accident. I'd be driving down the highway and I couldn't see what was coming because I'd have a memory flash. I haven't had it once since I wrote the story. You really do ground your nightmares, you name them. When you write a story, you have to play that image, no matter how painful, over and over until you've got all the sharp details so you know exactly how to put it down on paper. By the time you've run your mind through it a hundred times, relentlessly worked every tic of your terror, it's lost its power over you. That's what bibliotherapy is all about, I guess. You take crazy people and have them write their story, better and better, and soon it's just a story on a page, or, more precisely, everybody's story on a page. It's a wonderful thing. Which isn't to say that I think writing is done for the health of the writer, though it certainly does incidentally have that effect. INTERVIEWER Do you feel that literary techniques can really be taught? Some people feel that technique is an artifice or even a hindrance to true expression. ? GARDNER Certainly it can be taught. But a teacher has to

know technique to teach it. I've seen a lot of writing teachers because I go

around visiting colleges, visiting creative writing classes. A terrible number

of awful ones, grotesquely bad. That doesn't mean that one should throw writing

out of the curriculum, because when you get a good creative writing class it's

magisterial. Most of the writers I know in the world don't know how they do what

they do. Most of them feel it out. Bernard Malamud and I had a conversation one

time in which he said that he doesn't know how he does those magnificent things

he sometimes does. He just keeps writing until it comes out right. If that's the

way a writer works, then that's the way he had to work, and that's fine. But I

like to be in control as much of the time as possible. One of the first things

you have to understand when you are writing fiction—or teaching writing—is that

there are different ways of doing things, and each one has a slightly different

effect. A misunderstanding of this leads you to the Bill Gass position: that

fiction can't tell the truth, because every way you say the thing changes it. I

don't think that's to the point. I think that what fiction does is sneak up on

the truth by telling it six different ways and finally releasing it. That's what

Dante said, that you can't really get at the poetic, inexpressible truths, that

the way things are leaps up like steam between them. So you have to determine

very accurately the potential of a particular writer's style and help that

potential develop at the same time, ignoring what you think of his moral stands. 6. Harold Bloom - PR Interviews Vol 2 INTERVIEWER What do you think of creative-writing workshops? BLOOM I suppose that they do more good than harm, and yet

it baffles me. Writing seems to me so much an art of solitude. Criticism is a

teachable art, but like every art it too finally depends upon an inherent or

implicit gift. I remember remarking somewhere in something I wrote that I gave

up going to the Modern Language Association some years ago because the idea of a

convention of twenty-five or thirty thousand critics is every bit as hilarious

as the idea of going to a convention of 7. Toni Morrison - PR Interviews Vol 2 INTERVIEWER Do you think there is an education for becoming a writer? Reading perhaps? MORRISON That has only limited value. INTERVIEWER Travel the world? Take courses in sociology, history? MORRISON Or stay home ... I don't think they have to go anywhere. INTERVIEWER Some people say, Oh, I can't write a book until I've lived my life, until I've had experiences. MORRISON That may be—maybe they can't. But look at the people who never went anywhere and just thought it up. Thomas Mann. I guess he took a few little trips ... I think you either have or you acquire this sort of imagination. Sometimes you do need a stimulus. But I myself don't ever go anywhere for stimulation. I don't want to go anywhere. If I could just sit in one spot I would be happy. I don't trust the ones who say I have to go do something before I can write. You see, I don't write autobiographically. First of all, I'm not interested in real-life people as subjects for fiction—including myself. If I write about somebody who's a historical figure like Margaret Garner, I really don't know anything about her. What I knew came from reading two interviews with her. They said, Isn't this extraordinary. Here's a woman who escaped into Cincinnati from the horrors of slavery and was not crazy. Though she'd killed her child, she was not foaming at the mouth. She was very calm; she said, I'd do it again. That was more than enough to fire my imagination. 8. Alice Munro - PR Interviews Vol 2 MUNRO …I got an offer of a job teaching creative writing at York University outside of Toronto. But I didn't last at that job at all. I hated it, and even though I had no money, I quit. INTERVIEWER Because you didn't like teaching fiction? MUNRO No! It was terrible. This was 1973. York was one of the more radical Canadian universities, yet my class was all male except for one girl who hardly got to speak. They were doing what was fashionable at the time, which had to do with being both incomprehensible and trite; they seemed intolerant of anything else. It was good for me to learn to shout back and express some ideas about writing that I hadn't sharpened up before, but I didn't know how to reach them, how not to be an adversary. Maybe I'd know now. But it didn't seem to have anything to do with writing—more like good training for going into television or something, getting really comfortable with clichés. I should have been able to change that, but I couldn't. I had one student who wasn't in the class who brought me a story. I remember tears came into my eyes because it was so good, because I hadn't seen a good piece of student writing in so long. She asked, How can I get into your class? And I said, Don't! Don't come near my class, just keep bringing me your work. And she has become a writer. The only one who did. INTERVIEWER Has there been a proliferation of creative-writing schools in Canada as in the United States? MUNRO Maybe not quite as much. We don't have anything up here like Iowa. But careers are made by teaching in writing departments. For a while I felt sorry for these people because they weren't getting published. The fact that they were making three times as much money as I would ever see didn’t quite get through to me. 9. Peter Carey - PR Interviews Vol 2 INTERVIEWER These days you run a graduate writing program at Hunter College. But the way you became a writer was completely informal, right? You had no training. CAREY In one way that's true, but it would be too smug to go along with it uncritically. Yes, we tend to be self-taught, and there's a part of me that thinks that's the way it should be—you do it alone, you learn to endure loneliness. I never said, I think I'll just workshop this with twelve other people. But I did have help. I mentioned Barry Oakley, who'd been a schoolteacher. He encouraged me, he gave me books. He read my writing and infuriated me by telling me it didn't work. I somehow managed to cast him in the role of an old conservative father to my young radical. But when I wrote my first successful stories, he was the one who said, They're good. By then I couldn't bear to be rejected by anyone. Barry gave stories to this person and that person, and with his help they found their way into magazines. It wasn't an MFA program, but it was hugely helpful. If that had not happened I wouldn't have been a writer.

10. Kurt Vonnegut – Paris Review Interviews Vol 1 INTERVIEWER Do you really think creative writing can be taught? VONNEGUT About the same way golf can be taught. A pro can point out obvious flaws in your swing. I did that well, I think, at the University of Iowa for two years. Gail Godwin and John Irving and Jonathan Penner and Bruce Dobler and John Casey and Jane Casey were all students of mine out there. They've all published wonderful stuff since then. I taught creative writing badly at Harvard—because my marriage was breaking up, and because I was commuting every week to Cambridge from New York. I taught even worse at City College a couple of years ago. I had too many other projects going on at the same time. I don't have the will to teach anymore. I only know the .theory. INTERVIEWER Could you put the theory into a few words? VONNEGUT It was stated by Paul Engle—the founder of the Writers' Workshop at Iowa. He told me that, if the workshop ever got a building of its own, these words should be inscribed over the entrance: Don't take it all so seriously. INTERVIEWER And how would that be helpful? VONNEGUT It would remind the students that they were learning to play practical jokes. INTERVIEWER Practical jokes? VONNEGUT If you make people laugh or cry about little black marks on sheets of white paper, what is that but a practical joke? All the great story lines are great practical jokes that people fall for over and over again. INTERVIEWER Can you give an example? VONNEGUT The Gothic novel. Dozens of the things are published every year, and they all sell. My friend Borden Deal recently wrote a Gothic novel for the fun of it, and I asked him what the plot was, and he said, A young woman takes a job in an old house and gets the pants scared off her. INTERVIEWERSome more examples? VONNEGUT The others aren't that much fun to describe: somebody gets into trouble, and then gets out again; somebody loses something and gets it back; somebody is wronged and gets revenge; Cinderella; some body hits the skids and just goes down, down, down; people fall in love with each other, and a lot of other people get in the way; a virtuous person is falsely accused of sin; a sinful person is believed to be virtuous; a person faces a challenge bravely, and succeeds or fails; a person lies, a person steals, a person kills, a person commits fornication. INTERVIEWER If you will pardon my saying so, these are very old-fashioned plots. VONNEGUT I guarantee you that no modern story scheme, even plotlessness, will give a reader genuine satisfaction, unless one of those old-fashioned plots is smuggled in somewhere. I don't praise plots as accurate representations of life, but as ways to keep readers reading. When I used to teach creative writing, I would tell the students to make their characters want something right away—even if it's only a glass of water. Characters paralyzed by the meaninglessness of modern life still have to drink water from time to time. One of my students wrote a story about a nun who got a piece of dental floss stuck between her lower left molars, and who couldn't get it out all day long. I thought that was wonderful. The story dealt with issues a lot more important than dental floss, but what kept readers going was anxiety about when the dental floss would finally be removed. Nobody could read that story without fishing around in his mouth with a finger. Now there's an admirable practical joke for you. When you exclude plot, when you exclude anyone's wanting anything, you exclude the reader, which is a mean-spirited thing to do. You can also exclude the reader by not telling him immediately where the story is taking place, and who the people are— INTERVIEWER And what they want. VONNEGUT Yes. And you can put him to sleep by never having characters confront each other. Students like to say that they stage no confrontations because people avoid confrontations in modern life. Modern life is so lonely, they say. This is laziness. It's the writer's job to stage confrontations, so the characters will say surprising and revealing things, and educate and entertain us all. If a writer can't or won't do that, he should withdraw from the trade. INTERVIEWER Trade? : VONNEGUT Trade. Carpenters build houses. Storytellers use a reader's leisure time in such a way that the reader will not feel that his time has been wasted. Mechanics fix automobiles. INTERVIEWER Surely talent is required? VONNEGUT In all those fields. I was a Saab dealer on Cape Cod for a while, and I enrolled in their mechanic's school, and they threw me out of their mechanic's school. No talent. INTERVIEWER How common is storytelling talent? VONNEGUT In a creative writing class of twenty people anywhere in this country, six students will be startlingly talented. Two of those might actually publish something by and by. INTERVIEWER What distinguishes those two from the rest? VONNEGUT They will have something other than literature itself on their minds. They will probably be hustlers, too. I mean that they won't want to wait passively for somebody to discover them. They will insist on being read. INTERVIEWER You have been a public relations man and an advertising man — VONNEGUT Oh, I imagine. INTERVIEWER Was this painful? I mean — did you feel your talent was being wasted, being crippled? VONNEGUT No. That's romance—that work of that sort damages a writer's soul. At Iowa, Dick Yates and I used to give a lecture each year on the writer and the free-enterprise system. The students hated it. We would talk about all the hack jobs writers could take in case they found themselves starving to death, or in case they wanted to accumulate enough capital to finance the writing of a book. Since publishers aren't putting money into first novels anymore, and since the magazines have died, and since television isn't buying from young freelancers anymore, and since the foundations give grants only to old poops like me, young writers are going to have to support themselves as shameless hacks. Otherwise, we are soon going to find ourselves without a contemporary literature. There is only one genuinely ghastly thing hack jobs do to writers, and that is to waste their precious time. INTERVIEWER No joke. VONNEGUT A tragedy. I just keep trying to think of ways, even horrible ways, for young writers to somehow hang on.

11. Elizabeth Bishop PR Interviews Vol 1 INTERVIEWER Did you ever take a writing course as a student? BISHOP When I went to Vassar

I took sixteenth-century, seventeenth-century and eighteenth-century literature,

and then a course in the novel. The kind of courses where you have to do a lot

of reading. I don't think I believe in writing courses at all. There weren't any

when I was there. There was a poetry-writing course in the evening, but not for

credit. A couple of my friends went to it, but I never did.

12. Robert Stone Paris Review Interviews Vol 1 INTERVIEWER Aside from that childhood training in rhetoric, did you learn anything about writing in other academic programs? Anything useful or valuable about creative writing? STONE Not really. But a creative writing class can at least be good for morale. When I teach writing, I do things like take classes to bars and race tracks to listen to dialogue. But that kind of thing has limited usefulness. There's no body of technology to impart. But that doesn't mean classes can't help. The idea that young writers ought to be out slinging hash or covering the fights or whatever is bullshit. There's a point where a class can do a lot of good. You know, you throw the rock and you get the splash.

13. Richard Price Paris Review Interviews Vol 1 INTERVIEWER Can writing be taught? PRICE You can't teach talent anymore than you can teach somebody to be an athlete. But maybe you help the writer find their story, and that's ninety-nine percent of it. Oftentimes, it's a matter of lining up the archer with the target. I had a student in one of my classes. He was writing all this stuff about these black guys in the South Bronx who were on angel dust. . . the most amoral thrill-killers. They were evil, evil. But it was all so over-the-top to the point of being silly. He didn't know what he was talking about. I didn't know this stuff either, but I knew enough to know that this wasn't it.I said to the kid, Why are you writing this? Are you from the Bronx? He says, No. From New Jersey. Are you a former angel-dust sniffer? Do you run with a gang? He says, No. My father's a fireman out in Toms River. Oh, so he's a black fireman in suburban New Jersey? Christ! Why don't you write about that? I mean, nobody writes about black guys in the suburbs. I said, Why are you writing this other stuff? He said to me, Well, I figure people are expecting me to write this stuff. What if they do? First of all, they don't. Second, even if they did, which is stupid, why should I read you? What do you know that I don't know? He turned out to be one of these kids in the early eighties who was bombing trains with graffiti—one of these guys who was part of the whole train-signing subculture, you know, Turk 182. He wrote a story, over a hundred pages long, about what it was like to be one of these guys—fifteen pages alone on how to steal aerosol cans from hardware stores. He could describe the smell of spray paint mixing with that rush of tunnel air when someone jerked open the connecting door on a moving train that you were "decorating." He wrote about the Atlantic Avenue station in Brooklyn where all the graffiti-signers would hang out, their informal clubhouse, how they all kept scrapbooks of each other's tags. Who would know that stuff except somebody who really knew? And it was great. The guy was bringing in the news. Now, whether it's art or not depends on how good he is. But he went from this painful chicken scratch of five-page bullshit about angel-dust killers to writing stuff that smacked of authenticity and intimacy. That is the job of the writing teacher: what do you think you should be writing about? At Yale I had the same problem. They'd write ten pages of well-worded this or that, but where's the story? I finally came up with an assignment. I hate giving assignments. I hated getting them and I hate giving them. But—the last of the good assignments—I made them all find a photograph of their family taken at least one year before the writer was born. I said, All right. Write me a story that starts the minute these people break this pose. Where did they go? What did they do? We all have stories about our family, most of them are apocryphal, but whether you love or hate your family, they're yours and these are your stories. On the other hand, Tom McGuane once said, I've done a lot of horrible things in my life but I never taught creative writing.

In his book Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction, Vonnegut listed eight rules for writing a short story: Use the time of a total stranger in such a way that he or she will not feel the time was wasted. Give the reader at least one character he or she can root for. Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water. Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action. Start as close to the end as possible. Be a Sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of. Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia. Give your readers as much information as possible as soon as possible. To hell with suspense. Readers should have such complete understanding of what is going on, where and why, that they could finish the story themselves, should cockroaches eat the last few pages. Vonnegut qualifies the list by adding that Flannery O'Connor broke all these rules except the first, and that great writers tend to do that. submitted by Brett Wilson Reading novels seems to me such a normal activity, while writing them is such an odd thing to do.. .At least so I think, until I remind myself how firmly the two are related. First, to write is to practice, with intensity and attentiveness, the art of reading. You write in order to read what you've written and see if it's OK and, since of course it never is, to rewrite it: once, twice, as many times as it takes. You are your own first, maybe severest, reader. "To write is to sit in judgement on oneself," wrote Ibsen. Hard to imagine writing without rereading. But is what you've written straight off never all right? Yes, sometimes even better than all right And that only suggests, to this novelist at any rate, that with a closer look, or voicing aloud (that is, another reading), it might be better still. I'm not saying that the writer has to fret and sweat to produce something good. "What is written without effort is in general read without pleasure," said Dr Johnson, and the maxim seems as remote from contemporary taste as its author. Surely, much that is written without effort gives a great deal of pleasure. No, the question is not the judgement of readers - who may well prefer a writer's more spontaneous, less elaborated work - but a sentiment of writers, those professionals of dissatisfaction. You think: "If I can get it to this point the first go around, without too much struggle, couldn't it be better still?"And although the rewriting, and the rereading, sound like effort, they are actually the most pleasurable parts of writing. Sometimes the only pleasurable parts. Setting out to write, if you have the idea of "literature" in your head, is formidable, intimidating. A plunge in an icy lake. Then comes the warm part: when you already have something to work with, upgrade, edit. Let's say it's a mess. But you have a chance to fix it. You try to be clearer. Or deeper. Or more eloquent. Or more eccentric. You try to be true to a world. You want the book to be more spacious, more authoritative. You want to winch yourself up from yourself . You want to winch the book out of your mind. As the statue is entombed in the block of marble, the novel is inside your head. You try to liberate it. You try to get this wretched stuff on the page closer to what you think your book should be - what you know, in your spasms of elation, it can be. You read the sentences over and over. Is this the book I'm writing? Is this all? Or let's say it's going well; for it does go well, sometimes. (If it didn't, some of the time, you'd go crazy.) There you are, and even if you are the slowest of scribes and the worst of touch typists, a trail of words is getting laid down, and you want to keep going; and then you reread it. Perhaps you don't dare to be satisfied, but at the same time you like what you've written. You find yourself taking pleasure - a reader's pleasure -in what's there on the page. Blindwriters can never reread what they dictate. Perhaps this matters less for poets, who often do most of their writing in their head before setting anything down on paper. (Poets live by the ear much more than prose writers.) And not being able to see doesn't mean one doesn't make revisions. Don't we imagine that Milton's daughters, at the end of each day of the dictation of Paradise Lost, read it all back to their father aloud and then took down his corrections? But prose writers, who work in a lumberyard of words, can't hold it all in their heads. They need to see what they've written. Even those writers who seem most forthcoming, prolific, must feel this. (Thus Sartre announced, when he went blind, that his writing days were over.) Think of portly, venerable Henry James pacing up and down in a room in Lamb House composing The Golden Bowl aloud to a secretary. Leaving aside the difficulty of imagining how James's late prose could have been dictated at all, much less to the racket made by a Remington typewriter circa 1900, don't we assume that James reread what had been typed and was lavish with his corrections? When I became, again, a cancer patient two years ago and had to break off work on the nearly finished In America, a kind friend in Los Angeles offered to come to New York and stay with me as long as needed, to take down my dictation of the rest of the novel. True, the first eight chapters were done (that is, rewritten and reread many times), and I'd begun the next-to-last chapter, and I did feel I had the arc of those last two chapters entirely in my head. And yet I had to refuse his offer. It wasn't just that I was already too befuddled by a drastic chemo cocktail and lots of painkillers to remember what I was planning to write. I had to be able to see what I wrote, not just hear it. I had to be able to reread. Reading usually precedes writing. And the impulse to write is almost always fired by reading. Reading, the love of reading, is what makes you dream of becoming a writer. And long after you've become a writer, reading books others write - and rereading the beloved books of the past - constitutes an irresistible distraction from writing. Distraction. Consolation. Torment. And, yes, inspiration. Of course, not all writers will admit this. I remember once saying something to VS Naipaul about a 19th-century English novel I loved, a very well-known novel that I assumed he, like everyone I knew who cared for literature, admired as I did. But no, he'd not read it, he said, and seeing the shadow of surprise on my face, added sternly: "Susan, I'm a writer, not a reader." Many writers who are no longer young claim, for various reasons, to read very little, indeed, to find reading and writing in some sense incompatible. Perhaps, for some writers, they are. It's not for me to judge. If the reason is anxiety about being influenced, then this seems to me a vain, shallow worry. If the reason is lack of time, then this is an asceticism to which I don't aspire. Losing yourself in a book, the old phrase, is not an idle fantasy but an addictive, model reality Virginia Woolf famously said in a letter: "Sometimes I think heaven must be one continuous unexhausted reading.” Surely the heavenly part is that - again, Woolf's words - "the state of reading consists in the complete elimination of the ego". Unfortunately, we never do lose the ego, any more than we can step over our own feet. But that disembodied rapture, reading, is trancelike enough to make us feel ego-less. Like reading, rapturous reading, writing fiction - inhabiting other selves - feels like losing yourself, too. Everybody likes to think now that writing is just a form of self-regard, also called self-expression. As we're no longer supposed to be capable of authentically altruistic feelings, we're not supposed to be capable of writing about anyone but ourselves. But that's not true. William Trevor speaks of the boldness of the non-autobiographical imagination. Why wouldn't you write to escape yourself as much as you might write to express yourself? It's far more interesting to write about others. Needless to say, I lend bits of myself to all my characters. When, in In America, my immigrants from Poland reach southern California (they're just outside the village of Anaheim) in 1876, stroll out into the desert and succumb to a terrifying, transforming vision of emptiness, I was surely drawing on my own memory of childhood walks into the desert of southern Arizona, outside what was then a small town, Tucson, in the 1940s. What I write about is other than me. As what I write is smarter than I am. Because I can rewrite it. My books know what I once knew, fitfully, intermittently. And getting the best words on the page does not seem any easier, even after so many years of writing. On the contrary Here is the great difference between reading and writing. Reading is avocation, a skill, at which, with practice, you are bound to become more expert. What you accumulate as a writer are mostly uncertainties and anxieties. All these feelings of inadequacy on the part of the writer - this writer, anyway - are predicated on the conviction that literature matters. Matters is surely too pale a word. That there are books that are "necessary". That is, books that, while reading them, you know you'll reread. Maybe more than once. Is there a greater privilege than to have a consciousness expanded by, filled with, pointed to literature? Book of wisdom, exemplar of mental playfulness, dilator of sympathies, faithful recorder of a real world (not just the commotion inside one head), servant of history, advocate of contrary and defiant emotions. . . a novel that feels necessary can be, should be, most of these things. As for whether there will continue to be readers who share this high notion of fiction, well, "There's no future to that question," as Duke Ellington replied when asked why he was to be found playing morning programs at the Apollo. Best just to keep rowing along.

Who is buying the promises sold by writer's magazines? Dan Glover National Post

They could be mistaken for Cosmopolitan or Glamour, if not for the fact that the lacy come-ons on their covers promise a completed novel or sold poem rather than instant beauty or a thoroughly sated husband. Kneel before any city magazine rack, shift aside mildewed numbers of Rifle and Shotgun, Boy Bands and Fangoria, and you will find glossies like Personal Journaling, Scr(i)pt and The Writer, all promising to teach a gentler art than beauty or seduction -- the art of writing well, quickly. To the cynical, reading writing about how to write may seem like chasing one's own tail, but to others these magazines have become the holders of Masonry secrets, month by month decanting the distilled essence of the craft. The acknowledged master of the scene is Writer's Digest, a Cincinnati-based monthly with a circulation of 180,000. Established in 1920, when it appeared in the guise of a pulpy Reader's Digest, Writer's Digest long ago learned how to compete in a glossy, large-format world, marshalling a sense of desperate immediacy with peppy slogans -- 8 Sizzling Ways to Start Your Scene! or You Can Write a Great Novel! --- Extending hope where perhaps there should be none, these magazines are no favourites of the journals who receive the brunt of their readers' hopeful submissions. Asked about the 30,000 manuscripts that land annually on his magazine's slush pile, The Paris Review's Benjamin Howe responds by e-mail: "The job of sifting through them is handled by four or five readers, usually MFA students. These people, I've noticed, tend to leave the office at the end of the afternoon in a mute daze, which is the effect of reading so many fractured narratives. Less than a quarter of the manuscripts we receive are even somewhat publishable." Published writers, at least the kind who are invited to major short story conferences, also feel fiction takes more time. Speaking at the recent Wild Writers We Have Known symposium in Stratford, Ont., panellists said even the shortest stories linger a year or two at least before they assume a publishable form. In an example she acknowledged was extreme, writer Robyn Sarah recalled starting a story about a woman who veiled a suicide attempt as an accident, revealing her intent years later when she finally killed herself. Begun with a line scrawled on a piece of paper in 1975, the story took 18 years to finish, after an arduous struggle against half-starts, years-long blank spells and false victories. This was not how Sarah imagined writing would be, having inherited a mammoth box of issues of The Writer and Writer's Digest as a teen. "They made writing a story seem so easy, and it just didn't happen. I remember reading in Writer's Digest that the first draft of most saleable stories is written in one sitting. It wasn't so." To the audience, it seemed Sarah's point was not to claim every story requires a decades-long steeping, but that to write fiction is to enter into a pact without guarantees or deadlines, a view contrary to the school of thought that promises publishable manuscripts within 90 days. --- Writer's Digest is the foundation of an empire that has channelled the secrets of writing into every possible profitable form. Readers of Asimov's Science Fiction will have seen ads for the Writer's Digest Book Club, which sells everything from The Art of Compelling Fiction to You Can Write Greeting Cards, all with a value "up to $89.95!" Emergency room screenwriters can buy Code Blue; those with a taste for the law can get "an inside look at the U.S. legal system" via Order in the Court. The force behind these works is F&W Publications, a how-to giant that churns out fathomless numbers of books and magazines on art, design and woodworking. Like Alexander the Great, F&W must have surveyed the writer's advice market and wept because it had no more worlds to conquer. Bearing great block 'W's at the base of their spines, Writer's Digest volumes have stormed writer's shelves in bookstores everywhere, leaving nothing but a few scattered Strunk and Whites or Chicago Manuals of Style in their path. --- For those new to the territory, the ads in the writer's magazines seem a queer republic of their own, with all the gusto of traditional advertising but none of its polish. Leafing through Writer's Digest, one finds a spate of ads taken out by the makers of Kleenex™, Rollerblade™, Post-it™, Velcro™ and Wite-Out™, all petrified that writers will become tempted to use their names as nouns or, God forbid, gerunds. All respect for intellectual property aside, it is hard to envision a new wave of writers describing their heroes sniffling into "Kleenex™ brand tissue paper" when a single abused generic might do. The number of trademark ads, however, palls next to a series of darker pitches. Suggesting that anyone can write, perhaps for a price, scores of curious ads for vanity presses, ghostwriters, Christian guilds, correspondence courses and $40,000 poetry contests conjure a dimly lit parallel world where freelance secretaries still type out longhand manuscripts and agents in crisp, white, collared shirts linger at street entrances to publishing houses to push their latest discoveries. It is, of course, debatable whether this world exists. The agency and self-publishing ads seem always to lead to P.O. boxes instead of street addresses; and the correspondence courses originate in cyberspace rather than physical campuses. A case in point is a full colour ad that appeared in a recent Writer's Digest. There a sexless purple dinosaur leaps from a thin, waxy page, trespassing on Barney's intellectual content beneath the slogan, "We're looking for people to write children's books." In the small print, the advertiser reveals itself as The Institute of Children's Literature, a correspondence school that challenges writers to get in on the "more than $1.5 billion worth of children's books ... purchased annually." Based in Connecticut, the Institute awards six college credits per course and boasts a 95.2% student approval rate, a figure that would not seem awry in a North Korean election. Entering the world of children's publishing comes at a cost. When I called the Institute, a cordial operator named Sarah told me sending in my stories would cost $895 Canadian over 14 months, but said I would have at least one manuscript to submit to publishers by term's end. --- Although not as machine-like as Writer's Digest, many of its competitors have a deep history. The oldest is The Writer, a monthly born in Boston in April, 1887, with the stated goal of trying "to interest and help all literary workers." This year, the 20,000-circulation magazine was bought by Kalmbach Publishing, stripped of its editors and moved to Waukesha, Wis., a bedroom community just outside of Milwaukee. Kalmbach, the publisher of Model Railroader, Scale Auto Enthusiast, BEAD & Button and Astronomy, has sprung for a much-needed redesign and, hopefully, a staff that knows the correct spelling of Katherine Mansfield's name, one of many errors that dotted October's valedictory Boston edition. For all its flaws, The Writer seems to keep to a higher terrain than Writer's Digest, recommending voracious reading while discussing ways to climb out of artistic gullies. If behind its competitor's sugary slogans awaits a sour truth -- You will never write a novel -- The Writer whispers a gentler message: You might. Maintaining a more combative view is Toronto's Write magazine, whose editor, Chris Garbutt, calls his competitors "snake-oil salesmen" and Writer's Digest in particular "the Jenny Craig of writing" and an outlet for "career hobbyists." Recognizing that writing is an industry of hope -- and hope is easily preyed upon -- Write recently published editorials decrying submission guidelines and the fly-by-night literary contests that charge writers vast fees to enter their work. "We take writing a lot more seriously and a lot less cynically," Garbutt says. "These other magazines get your money and get out of town." --- Writer's Digest editor Melanie Rigney says her magazine occasionally rejects the ads of companies it feels have abused the trust of readers -- outfits she calls "rip-off people, the Edit Inc.s of the world who really made people think that if they used these editing services, their books would be published." While Rigney says Writer's Digest accepts no payment for its workshops, the magazine does run ads for the Writer's Digest Criticism Service, a "tailored advice" program that charges US$46 for the first 3,000 words of a story, and US$8 for every 1,000 words thereafter. She adds the magazine has a "Church and State" policy in which the advertising department has no inside view of the editorial product, but admits vetting advertisers has become "kind of a balancing act." --- All the evidence points at Writer's Digest encouraging a class of writers who seek a quick, tidy profit -- quite hopelessly. Beneath stories of first successes and pie-in-the-sky paydays (US$75-$125 an hour for brochure-writing; US$130-200 per page for white papers), the magazine buries listings that offer better assessments of what journals pay -- Murderous Intent US$2-$5 per poem, Century four cents per word for fiction, The Leading Edge a single cent for prose. More lost hope is apparent in a Writer's Digest column called "Writer's Clinic." Chosen from a pool of approximately 30 to 50 submissions, the four pages critiqued in the September issue are marked by dialogue as level, colourless and well-drained as the Bonneville Salt Flats. Although the work is entirely without merit, the Writer's Clinic editor refuses to say so, gravely advising his charge to evoke character by using verbs like "scurries," "sweeps" or "strides." An outsider cannot help but see a greater flaw in the story: that it is painful to read. The problem the editor avoids is evident -- and, if acknowledged, endangers the life of his magazine. A novel, any good novel, whether an intellectual romance, a satire, a potboiler or a thriller, begins with a line that works, a line tense and rare enough to pull the reader to the next line. The lines resolve into paragraphs, the paragraphs into chapters, the chapters eventually into the vaster work, the novel. Only the greatest page-turners are able to exploit this truth, which is why there are so few of them. The rest, no matter how hard they try, cannot tug readers so forcibly from line to line. --- There is another point of view, one that heralds writing as an act of observation and expression, regardless of whether it leads to publication -- an act that exists in a chorus alongside reading and thinking. "I think that writing is one of the most important artistic endeavours," says Write's Garbutt. "Whether you're writing a cute little memoir or a political treatise, I think that writing is a political act. "Should everyone write? Why not? Should everyone get published? Probably not." For all the criticisms aimed at the writer's advice magazines, their audience is indisputably loyal -- or at least well-poised in a renewable industry of hope. In a craft that traces its roots to prophets and soothsayers, few writers like to admit that they have taken inspiration from lesser sources, let alone from low-cal glossies at the base of magazine stands. Still, while James Joyce may have been a genius from the cradle and William Faulkner motivated enough to write As I Lay Dying over four weeks of night watchman shifts at a power plant, other storytellers needed to be taught and inspired, such as Flannery O'Connor and J.D. Salinger, whose writing flourished after they entered workshops. As improbable as it might seem, the writer's magazines may hint at a truth. For all the forms our literature admits, there may still only be "8 Sizzling Plots" or "2 Foolproof Endings" -- with our best proof the generations of novelists who use comedy or tragedy as a backbone, and can't finish a book unless wedding or funeral bells are cascading in the distance.

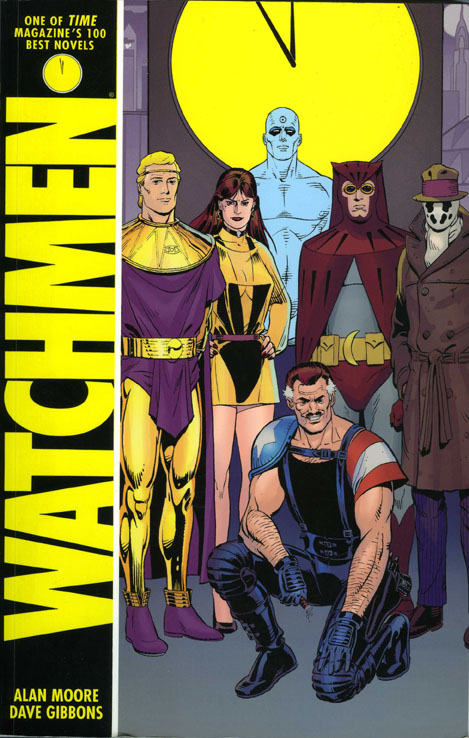

Amazon ReviewersI first delved into the reviews posted by readers on Amazon.com for utilitarian reasons. I will soon be publishing a serious nonfiction book; I wanted to know what kind of attention such a book could expect to get from this particular sample of the reading public. My case study, I decided, would be Susan Faludi's Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man. I came, I clicked, I read. Stiffed, as of this writing, has been reviewed by 75 Amazon.com users. Quite a few pieces were thoughtful and well-turned, often outstripping in quality the capsule reviews that run in outlets like Booklist and Library Journal. I began availing myself of the feature that lets you see all the other pieces a particular reviewer has posted, and a brief autobiography. There was the man who has devoted his retirement to the study and practice of social criticism; the "graying engineer" who recommended Stiffed to his fellow Promise Keepers; the environmental science student at Rice University whose searching reviews of such works as the Koran, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, and an entire shelfful of books attempting to refute the theory of evolution provided a moving portrait of a sensitive mind composing itself into maturity. The part of me that instinctively defends Average America against charges of numskullery--my inner populist--was gratified indeed. Then I was visited by my inner Reinhold Niebuhr. That happened when one anonymous writer, after several insightful paragraphs on the Faludi book's pros and cons, veered off into an unhinged rant about the evils of the alimony system. I now glanced over the 75 reviewers with different eyes, saw that many of them, perhaps a plurality, were eaten away by resentments of "this new matriarchy we are suffering with" and "another foaming-at-the-mouth denunciation of men." But they, too, got me going: Plumbing such depths is something a chair-bound intellectual anxious about losing touch with the real world can always enjoy. I was, at any rate, hooked. Amazon.com was interesting. I spent the better part of a month absorbed within what can fairly be called its culture. Amazon ranks its reviewers via a complex algorithm based on the number and popularity of their reviews, and, besotted by Malcolm Gladwell-think, I hit upon the brilliant idea of finding reviewers to whom--through whom--I might promote my own book. I soon discovered that top Amazonians are far too busy to countenance such a nuisance. The first-place reviewer earned a profile in People by reviewing over 670 books in five years--15 over one five-day stretch. Another's reading is booked through the next decade. A third clawed his way to 17th place by writing word-splicing reviews in analytic philosophy mode, 22 in the month of May alone, on the likes of Spinoza and Hume. ("If his distinction between 'personal' and 'impersonal' values is also found wanting," he observed of Thomas Nagel, "then his argument is an extended ignoratio elenchi." But you knew that.) I wondered why they did it. So I began to get to know them. Some are possessed of a simple sense of craft and calling. One of my favorites, a Proust fan and student of superstring theory, described to me the centerpiece of his elaborate reading room: a sculpted recumbent leather chair that holds him "sort of in a spaceship takeoff position." He marvels that house guests see nothing in wandering in and engaging him in conversation when he is so ensconced. "I suppose to most Americans," he complains, "reading is what you do when you haven't anything better to do." Others' motives are not so pure. A general contractor who calls himself Toolpig--people review all kinds of consumer products on Amazon, not just books--explained to me that he had been happily rating tools for years simply for the pleasure of helping others. Then, this spring, he received an e-mail from Amazon honchos informing him that they would soon be inaugurating the rankings program and that he was among the site's top reviewers. Before that, he was planning to retire. "Now it's different," he says. "I've been ranked. I love competition." From writers Amazon.com often gets poor reviews. "It may mark an excessive surrender to the anonymous mind-suckers who inhabit the Internet these days to give any credit to the amateur 'reviewers' who comment on new books via Amazon.com," wrote novelist Rosellen Brown in a recent issue of The Women's Review of Books, "but they're a nasty fact." I can see from whence her anger springs. Brown's novels harvest praise in Time and The New York Times Book Review, blurbs from people like Cynthia Ozick and Anne Tyler, but on Amazon, she's something of a goat. "Shallow and somewhat insulting," is one typical verdict; "so frustrating in its obviousness that the novel is almost unreadable," is another. Amazon wears away all those insulating cushions--reviews by relatively thoughtful professionals, cosseting praise from friends and family, readings before fans (never critics)--that have ever protected authors from the outrageous opinions of poor, indifferent, or even hostile readers. Who are perhaps, even, the majority of readers. Our public: Take them or leave them. Though a surprising number of Amazon reviewers are professional writers themselves. Did I mention one of the reviewers of Stiffed was Nation columnist Katha Pollitt? Her 14 reviews of nonfiction, fiction, poetry, and children's books are enough to earn her 1,966th place in the Amazon rankings--only 256 spots behind Newt Gingrich. It's the glaring, almost structural, discontinuity of interest between readers with clout and readers on Amazon that is most fascinating. You see it again and again: Books reviewed "everywhere"--the kind of books a print addict feels like he or she has read even without cracking the spine--do not make a ripple here. Bosie: A Biography of Lord Alfred Douglas, a ballyhooed title from the spiffy new conglomerate Talk Miramax, has been reviewed once. The gap may be widest in the realm of politics. The Amazon page for Paul Berman's '60s study, A Tale of Two Utopias, excerpts five glowing reviews from newspapers and magazines but not a single one from an Amazonian; John Judis's new book has six print reviews to one Amazonian. Books about Clintons and Reagans are well-covered. Gary Aldrich's Unlimited Access: An FBI Agent Inside the White House has been reviewed on Amazon 70 times, garnering, like most conservative books, 80 percent five-star ratings and 20 percent one-star, as opposed to pro-Clinton books, which receive 20 percent five-star, 80 percent one-star. In both cases, the quality tends to be as debased as ... well, the typical political campaign. We get the political reviews we deserve. Amazon rewards its top reviewers with gift certificates and "Amazon.com Top Reviewer" knickknacks. No surprise; this is their sales force. But it is also so much more: a political commons, a fairly extraordinary congeries of demotic expertise, a semi-spontaneous system of pools, eddies, and currents--the more dynamic the more people participate. Writers stake out niches--five-star business books, fine collectibles guides, Regency romances, the Final Solution. University of Massachusetts economist Herb Gintis's page constitutes an excellent lesson plan for the student of evolutionary game theory, an increasingly important sub-neck-of-the-woods for social scientists. Some cater to still more esoteric tastes--like Rabbi Yonassan Gershom, who uses his presence in the top 100 to promote a site featuring "the Web's most extensive FAQ on cases of reincarnation from the Holocaust period." Barron Laycock is a daunting expert in twentieth-century European history (whose other reviews, however, draw hate mail from feminists); Duwayne Anderson is on a mission to spread the word on all the science books he has discovered since abandoning the intellectual strictures of his former Mormon faith. At first it hardly seemed romantic to imagine the site might go on of its own steam, even if the commercial enterprise were to collapse tomorrow. But then I heard from a few late respondents. Amazon's volunteers are constrained from the start, it emerges. All reviews are evaluated by corporate personnel before they are posted. Personal attacks are (imperfectly) screened out; more portentously, negative reviews are often disallowed unless the writer recommends some alternative purchase. As for the ranking of reviewers, thoughtful observers are beginning to agree--even as they are left unclear how this occult scheme actually works--that it is becoming irredeemably corroded by various ways of gaming the system. (Attract, for example, a flock of friends to praise your two-word review, "cool music," and you advance dramatically.) "The reviewers were invited to become a community," one of them told me, "and then the community was handed over to thugs." Our Amazonians, ourselves--honorable, vulnerable, both. "If men were angels," said James Madison, "no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary." Whether as book reviewers or as citizens, people are as good as the rules they work within; make the rules progressively worse--as excessive concern for money tends to do--and "cool music" (or, to take another example, campaign finance hogs like Senator Mitch McConnell) soon enough set the standard. We, meanwhile, are left to our own critical faculties to find richness among the ruins--which is all we ever had. And if there's a new book on World War II you want to size up, let me recommend to you a visit to Barron Laycock's page on Amazon, because he's already been there. ¤ The Growth of the Poet's Mind #1 Brett Wilson The books that make a difference are the ones you remember. These are the books that define your life, set you off in new directions, and influence your style. I still own the first comic book I bought: Thor #141: The Wrath of Replicus. Many would decline that to call it a book. But the majestic graphics of Jack Kirby do not detract from the quality of Stan Lee’s words. I was eight years old. When I think of the disdain with which my teachers treated comics, I feel sorry for those boys who were turned off books but didn’t have a marvel such as this. The writing alone surpasses anything offered to an infant in our unimaginative system of one size fits all education. Robert E Howard could create atmosphere like the best gothic novelists and to this he added action and narrative drive. Colin Wilson’s book, The Occult was my template for essay style along with Thomas Carlyle’s Heroes and Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy. Lao Tse’s Tao Te Ching didn’t start my interest in mysticism but it is concise, beautiful and deeply perplexing. David Hume’s challenge in A Treatise of Human Nature was not met by me, nor by any other thinker. He successfully undermines empiricism and the collective project of science (fortunately he was ignored). As a young man I was depressed by this idea, as I was by Kurt Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. The idea of automating theorem production (first proposed by David Hilbert) and hence automating thought, seemed like a prize within reach, but Gödel showed that the enterprise was a chimera. Wittgenstein had already abandoned his picture theory of language proposed in the Tractatus Logico Philosophicus, and Turing in his doctoral thesis was able to show how the halting problem delimited classical computation. I was always fascinated by the spastic narrative. What Kurt Vonnegut does in Slaughterhouse Five is make it serve the story. The resignation and black humour chime with the inhumanity of war. CH Waddington was a member of the Club of Rome, a group with the avowed aim of diverting humanities advance toward a Malthusian demise. In Tools for Thought he explores the problems in describing complexity, in the fashion of his inspiration D’Arcy Thomson. After reading this book I realised that this was in essence the fundamental intellectual problem, more relevant than cosmology or particle physics. The Wasteland by Thomas Eliot was my template for poetry, later to be modified by Hopkins’s alliteration, Auden’s use of the preposition and to some extent by Keats and Blake. I read Shakespeare’s Hamlet like an obsessive compulsive and the Sonnets still live in my top pocket. The siren Conjectures and Refutations by Karl Popper called to me from a second hand book shop (now a hair dressers) on Broadstone Road in Heaton Moor. ‘Read me’ it whispered, with its sisters Bricks to Babel by Arthur Koestler and The Ascent of Man by Jacob Bronowski. Survival Into the Twenty First Century gave me a recipe for practical mysticism. The basic proposition is: eat raw food to become spiritual. It’s not that simple, and the book is deeply flawed in the way that it uses evidence to support various beliefs. The book doesn’t know what it wants to be. But my fatal attraction is for books. I loved this crank. What Do You Say After You Say Hello? is by Eric Berne. Less well known than The Games People Play, but is the one that defines transactional analysis, a sort of structural Freudian psychology. It seems simple now but its simplicity is still useful. Novels don’t get much of a look in on this list but Waterland by Graham Swift is exceptional. It is everything I enjoy in a long story: temporal fluidity, atmosphere, characters, detail and a span of generations, the disjunction between story telling and recording, embedding story in record and record in story. When I was a boy I used to write encrypted messages. FL Bauer wrote a book for the man that used to be that boy and Decrypted Secrets is a joy of concision. A New Kind of Science makes big claims, has been severely criticised for not sharing credit, but is a book that could shift the method of science away from the empirical root exemplified by Bacon and Galileo. It is the heir to Tools For Thought. The Computational Beauty of Nature is almost the companion volume to A New Kind of Science. Its subject matter is broader. Stephan Wolfram uses one dimensional cellular automata to analyse complexity while Gary Flake revels in variety. Like The Fabric of Reality by David Deutsch (although less explicitly), it is suggestive of a link between evolution, virtual reality and complexity theory. Watchmen is the third novel on my list, although some would not accept that classification. The Crazy Oik was created by the slightly batty Kenneth Clay, who I am expecting to join me in Bedlam soon. His creation reminds me that there is talent all around and that surmounting the publication lottery was only possible for the rich and their cronies, and for the well connected – no more…. The creation of The Crazy Oik is an act of generosity.

Thor #141 “The Wrath of Replicus” Jack Kirby/Stan Lee Age 08 Conan the Adventurer Robert E. Howard Age 14 The Occult Colin Wilson Age 16 The Waste Land T.S. Eliot Age 18 Tao Te Ching Lao Tse (trans J Legge) Age 20 Hamlet and the Sonnets William Shakespeare Age 21 A Treatise Of Human nature David Hume Age 23 Slaughterhouse-Five Kurt Vonnegut Age 24 Tools for Thought C.H. Waddington Age 26 On Formally Undecidable Propositions… Kurt Gödel Age 27 Conjectures and Refutations Karl Popper Age 28 Survival Into the 21st Century Viktoras Kulvinskas Age 29 What Do You Say After You Say Hello? Eric Berne Age 31 Waterland Graham Swift Age 35 The Ascent of Man Jacob Bronowski Age 43 Decrypted Secrets FL Bauer Age 44 A New Kind of Science Stephan Wolfram Age 47 Computational Beauty of Nature Gary Flake Age 48 Watchmen Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons Age 49 The Crazy Oik Ken Clay (ed.) Age 50 Thor #141 “Who is Replicus?” Jack Kirby/Stan Lee Age 8

I was just a sprog, fresh off the oik block. I read the Beano and played with rubbish on the back field. But then something came to awaken me from my dogmatic slumbers. It was time for the yearly holiday and Mum and Dad had got us all onto the local boneshaker direct to Victoria Station Manchester where we were due to be whisked off to sunny Abergele in a big chuff chuff. I was hauling a huge old suitcase, twice my weight, as usual. For once we weren’t late and I managed to sneak off to the small book/magazine stand where my eyes feasted for the first time on what would be an obsession until my early twenties. I lived in grey Manchester you see. This was the time when all moths were speckled brown, to match the grime festooned walls. Even the sparrows had a poorly chest. TV was black and white and our first fridge was three years away, the telephone four. Another thing: in those days you left childhood as early as possible. If that meant wearing a Mac and slicking your hair back then so be it. Adults didn’t extend their childhood as they do now. No, they were serious. Now I was hypnotised, wide eyed before these pages soaked in colour, and ready to stay in childhood forever. Superheroes, gods, aliens and robots. They (Marvel comics) even threw in a good hearted crime boss. It was also my first encounter with American hyperbole delivered by the master of melodrama, Stan-the-man. It was Lee (or Lieber if you prefer) who brought day to day concerns out of soap opera and into comics. That is why Spiderman is neurotic and has an ulcer, the Fantastic Four worried about fame and the X-men were subject to prejudice. All Superman worried about was who was packin’ kryptonite. I mustn’t forget Jack Kirby (the artist). Kirby is able to capture motion so perfectly, you can feel it. Many of his hero’s poses are so primal they gouge appreciation out of your chest. I should also mention that other great penciller Steve Ditko, who drew Spiderman like an anorexic and made Dr Strange wander psychedelic lands just as LSD was hitting the streets. But that’s for another time…. Conan the Adventurer Robert E. Howard Age 14